Who is elected in law enforcement?

Key Takeaways

- Recent protests about ongoing and systemic police violence have sparked a national conversation about racism in policing and the need for police reform.

- Elections are one way for the public to hold law enforcement accountable and have a say in criminal justice policy. Unfortunately, like other elections at the state and local levels, turnout for key law enforcement positions is generally low.

- Depending on where they are located, voters can influence public policy on policing and hold certain law enforcement positions accountable through the election of several key positions: police chiefs, sheriffs, attorneys general, municipal prosecutors, and judges.

- Increased public attention on policing can have an impact on criminal justice reform, but it is unlikely without additional civic education on the roles of elected law enforcement officials and the issue positions of candidates, as well as sustained efforts to increase turnout in local and state-level elections.

In recent years, policing has become a central political question in the United States due to growing awareness about police brutality and racial discrimination in law enforcement. Following several highprofile police murders of Black Americans, including Michael Brown and Tamir Rice in 2014, Freddie Gray in 2015, Philando Castile in 2016, and Breonna Taylor in 2020, the killing of George Floyd in 2020 sparked nationwide protests and a broader conversation about systemic racism in policing and the need for police reform. The protests have led to calls for rethinking the role of police in society, increasing accountability and transparency, and addressing systemic biases in the criminal justice system. This has resulted in debates at the local, state, and national levels about the appropriate use of force by police, the need for more diversity and community engagement in policing, and the need for greater accountability for police misconduct. In this political climate, the issue of policing raises questions about civil rights, public safety, and the role of government in ensuring justice for all citizens.

The relationship between policing and democracy is complex. In a democratic society, the police are supposed to serve and protect the people rather than operate as an independent power. Policing in a democracy should uphold the principles of accountability, transparency, and respect for individual rights and freedoms. But policing has often fallen short of these democratic ideals, particularly in communities of color. Policing can even pose a threat to democracy if it is used in a way that violates individuals’ civil rights and freedoms.

Recent debates over policing in the U.S. highlight the need to reimagine policing in a democratic society. How can we bring our democracy to bear on policing and law enforcement in the U.S.? In the first of a larger series on law enforcement and democracy, we at Public Wise highlight community law enforcement that voters have the most ability to influence: those elected directly to public office.

The connection between policing and democracy has often been neglected in part because criminal justice policy is shaped mainly at the local and state levels. Elected law enforcement officials often run unopposed; even when challenged, incumbents almost always win. Low turnout – one of the defining features of local elections in the United States – – leads to low accountability in local politics. Perhaps the most important barrier to turnout is the low level of knowledge that most voters have about local politics: It is hard for voters to hold candidates accountable if they do not know candidates’ issue positions (Sances 2018, Meeks 2020) or what policies they are responsible for (de Benedictis-Kessner 2018).

Understanding the roles of elected officials who shape policing in the U.S. is especially confusing because the law enforcement system itself is complex, with jurisdictions operating at the federal, state, and local levels. The most common type of law enforcement that a person encounters on a day-to-day basis are local law enforcement agencies, such as city and county police departments, which are responsible for enforcing laws and maintaining order within their jurisdiction. City and county policing units may operate separately in the same geographic area. Adding to the complexity is the variation there is from place to place. Depending on where you are in the U.S., the exact setup governing who runs the police and who enforces the law will look slightly different and may use other names, even for the same roles.

But this lack of voter influence on elected law enforcement officials is changing. In recent years, there has been a push to pay more attention to who is elected to law enforcement. In 2016, an ever-increasing awareness of prosecutors’ authority swept a wave of young, diverse, reform-oriented prosecutors into office, and this movement has continued into every election held since then. Described as the “the New D.A.s,” they have been championed by a number of high-profile politicians and activists.

But whether the new attention on municipal politics will yield fruit for criminal justice reform remains yet to be seen. It will require more voters to make their way to the ballot box in city and county elections. Understanding which elected officials pull the levers of law enforcement is the first step to understanding how you can influence criminal justice with your ballot.

Police Chiefs

Police chiefs are in charge of overseeing the operations of the police department of a city. They liaise between the department and the municipal government and are responsible for disciplining police officers. They also have a great deal of leeway in deciding what data gets collected on incidents like officer-involved shootings (Robinson 2020).

Most police chiefs are appointed by elected officials in municipal governments. But in some smaller cities, especially in Louisiana, they may be directly elected to office during municipal elections. These elections in the U.S. are typically held every four years, but the timing varies from place to place. Unfortunately, despite the high level of influence these elections have over law enforcement, they often receive less attention than federal and state elections and usually have relatively low voter turnout.

Sheriffs

Sheriffs are considered the top law enforcement officers in their jurisdiction, typically counties. Since jails are often the mandate of the county (cities often have more temporary detention facilities), your vote for sheriff likely decides who runs the local jail and what the conditions in the jail will be. Sheriffs also have the authority to decide whether your local jurisdiction collaborates with immigration authorities, and their personal attitudes towards immigrants have been shown to shape local immigration policy (Farris and Holman, 2016). Increasingly, they have organized as a group to lobby against police reform efforts.

Some strongman sheriffs have started to get more of a national spotlight, highlighting the immense amount of power those in this position hold. Joe Arpaio, who presided over the police department of Maricopa County, Arizona until 2016, became known nationwide for his aggressive stance on illegal immigration, which included conducting “sweeps” in Latino neighborhoods and setting up a special unit to enforce immigration laws.

Sheriffs are usually voted in at the county level, but their term lengths and when they are elected vary from state to state. Despite being one of the most influential political office-holders in any given county, especially in rural areas, sheriffs often face little competition once elected to office. Research shows that sheriffs have a substantial incumbency advantage in elections: An incumbent sheriff has a “45 percentage point boost in the probability of winning the next election – far exceeding the advantages of other local offices” (Zoorob 2022). Relative to appointed police chiefs, sheriffs hold office for twice as long.

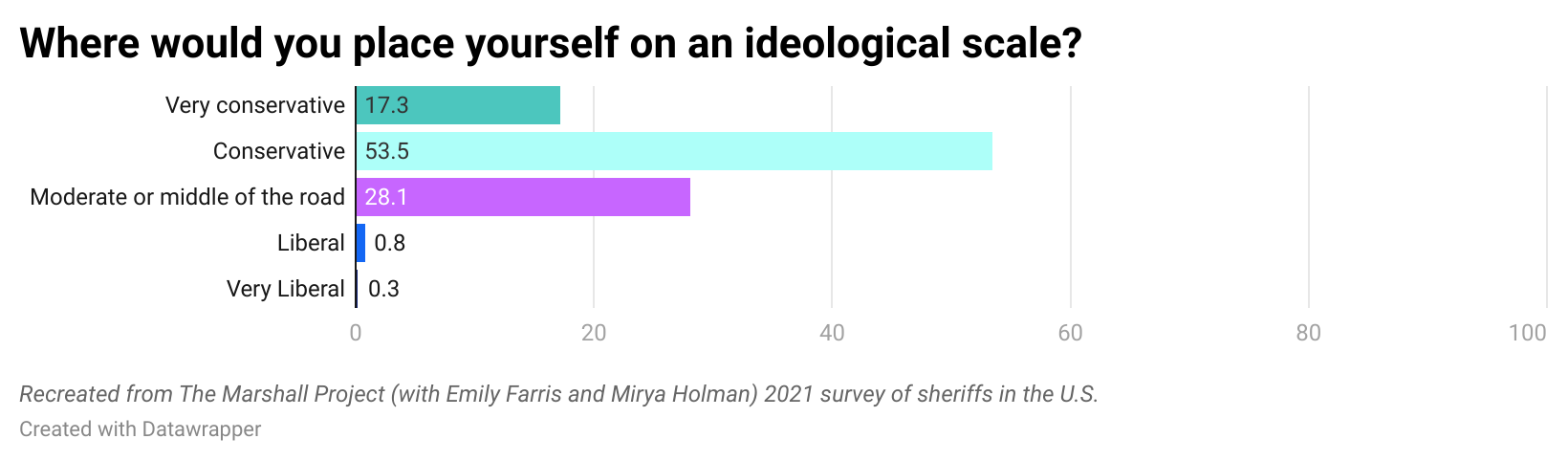

Researchers have also shown that sheriffs as a group have a particular ideological bent that is far to the right of the nation as a whole. The Marshall Project found that over 70% of sheriffs identify as conservative or very conservative.

Some sherrifs races have recently become more competitive, with anti-Trump challengers entering races against long-standing hawkish incumbents (Zoorob 2020).

Governmental Attorneys

The U.S. government employs many different types of attorneys who are charged with prosecuting crimes and representing the government in court cases. Most attorneys who work for the government are appointed, but a select few who serve as the head of their jurisdiction at the federal, state, or municipal level, are elected directly by the public.

Attorneys General (State’s Attorneys)

The Attorney General is the top lawyer for a government, typically at the state or federal level. The duties of an Attorney General include acting as the chief legal advisor to the executive branch and providing guidance on various legal issues. They enforce state and federal laws within their jurisdiction and may lead investigations and bring charges against individuals and entities that violate the law. Attorneys General also may defend government actions and policies when challenged in court. They can also use their position to advocate for the public interest on issues such as civil rights, environmental protection, and public health.

While often thought of as a bureaucratic position, attorneys general have quite a bit of discretion on which laws they must defend and how. State attorneys have become increasingly influential in the context of the U.S.’ fragmented federal system, and more aggressive state attorneys general have taken on a proactive position in challenging federal law enforcement policies and shielding state regulation from federal oversight (Mather 2003). Some legal researchers have described them as “national lawmakers” (Clayton 2009).

The most prevalent method of selecting a state’s attorney general is by popular election, although in seven states they are appointed. They run on a partisan basis in state-level elections, and typically serve a four-year term.

Municipal Prosecutors (District Attorneys / County Attorneys)

A municipal prosecutor is a lawyer representing a city or town government in criminal cases within that jurisdiction. They are responsible for prosecuting traffic violations, misdemeanors, and local ordinance violations in local courts. In many larger jurisdictions, they prosecute all state and local crimes from misdemeanors up to felonies that occur in that jurisdiction, as well as represent the jurisdiction in civil suits, whereas in other smaller jurisdictions, they might only handle preliminary felony hearings.

Municipal prosecutors may also be involved in plea bargaining and negotiating settlements in certain cases. The municipal prosecutor’s decisions on which cases to prosecute, how to negotiate plea bargains, and what charges to bring can impact the outcome of cases for individuals and for the larger community. They also play a role in setting local priorities and determining the resources allocated to criminal justice initiatives. There are also smaller jurisdictions where the county attorney has no role in prosecution but acts as the legal council for the county.

The public often underestimates the influence prosecutors have on the criminal justice system in the United States. More than nine out of every 10 cases are resolved by a plea bargain, meaning a judge has little or no role. Additionally, prosecutors often unilaterally decide who gets a second chance and their charging decisions often determine what sentencing looks like because of mandatory minimums associated with certain crimes. They often also exhibit a great deal of influence in state legislatures. Prosecutorial opposition has been able at times to undermine even modest attempts at criminal justice reform.

Prosecutors are elected, but have historically had little oversight between elections. They are typically charged with proposing the law enforcement budget in their jurisdiction, and their budgets are often approved with little pushback. At the legal level, they enjoy broad immunity from lawsuits in many cases.

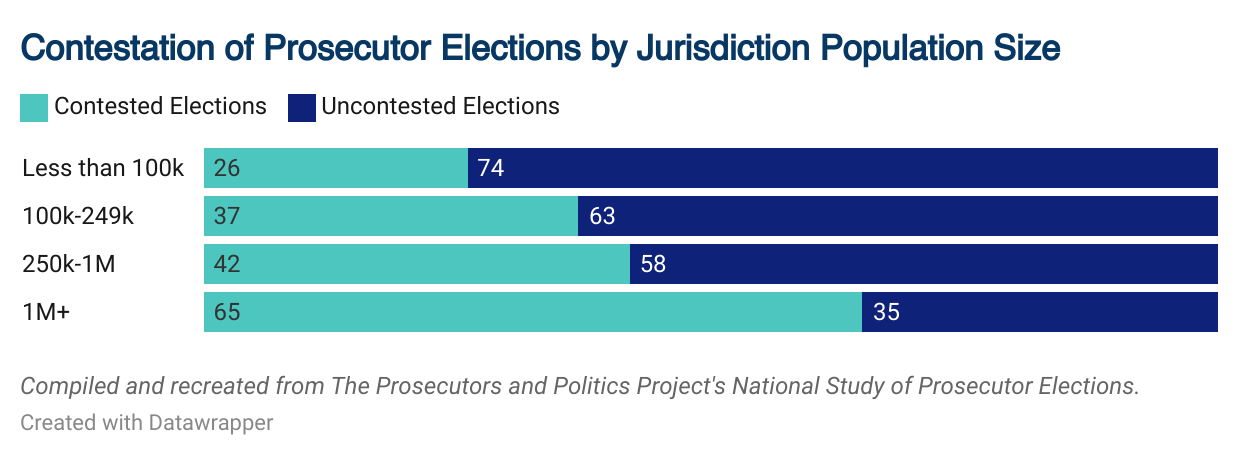

Even in elections themselves, there has often been little accountability. In 2016, more than 70 percent of prosecutors ran unopposed, and these offices have a strong incumbency advantage.

Most recent election since 2020; Source: National Study of Prosecutor Elections

State attorneys are generally elected in 43 states, and most serve four-year terms. District attorneys typically serve four-year terms as well; unlike state-level prosecutors, they’re either elected at the city or county level. Municipal prosecutors for cities are typically elected in municipal elections.

Judges

Trial judges hear individual law cases, decide on charges, set bail amounts in criminal courts, and determine the sentences of those deemed guilty. Your vote can shape whether the criminal justice system focuses on punishment or rehabilitation and how lengthy the sentences are for different crimes.

Judges’ positions are filled by a wide range of different types of appointments and elections, but 39 states use some kind of election in selecting judges.

There’s no unified process for electing judges, although they are elected in most states. In some states, judicial candidates are required to run on a party line while other states exclusively have non-partisan elections. Some states have a mix of both. Term lengths also vary by jurisdiction, but typically range from six to 10 years, among the longest term lengths for any elected office in the U.S., it is unusual for incumbents to face opposition. Surprisingly, 32 states do not require a legal background to serve as a judge.

Interestingly, despite judges often running on a partisan line, some research finds no differences between elected judges’ rulings regardless of political orientation (Lim, Silveira, Snyder 2016). The same has not been found, however, for judges appointed by an elected official of a given party (Gormley, Kaviana, Maleki 2020). This could be because judges elected directly are often subject to the scrutiny of an exceedingly small percentage of the electorate, since just about a fifth of the population ever casts a ballot for judicial races (Geyh 2003), public attention is brought to judges’ rulings only in exceptional cases (Baum 2003), and judicial elections tend to have large incumbency advantages (Olson 2022).

Elected Officials Outside of Law Enforcement

Of course, these are not the only elected officials who shape the face of criminal justice policy in our country. In Part Two of our series on policing and democracy, we discuss the elected officials outside of law enforcement who influence policing policies.

Summary prepared by Ella Wind, PhD.

Academic References

Baum, Lawrence. 2003. “Judicial Elections and Judicial Independence: The Voter’s Perspective.” Ohio State Law Journal 64(1).

de Benedictis-Kessner, Justin. 2018. “How Attribution Inhibits Accountability: Evidence from Train Delays.” The Journal of Politics 80(4): 1417–22.

Clayton, Cornell W. 1994. “Law, Politics and the New Federalism: State Attorneys General as National Policymakers.” The Review of Politics 56(3): 525–53.

Farris, Emily M., and Mirya R. Holman. 2017. “All Politics Is Local? County Sheriffs and Localized Policies of Immigration Enforcement.” Political Research Quarterly 70(1): 142–54.

Geyh, Charles G. 2003. “Why Judicial Elections Stink.” Articles by Maurer Faculty 338.

Lim, Claire S.H., Bernardo S. Silveira, and James M. Snyder. 2016. “Do Judges’ Characteristics Matter? Ethnicity, Gender, and Partisanship in Texas State Trial Courts.” American Law and Economics Review 18(2): 302–57.

Mather, Lynn. 2003. “The Politics of Litigation by State Attorneys General: Introduction to Mini-Symposium.” Law & Policy 25(4): 425–28.

Meeks, Lindsey. 2020. “Undercovered, Underinformed: Local News, Local Elections, and U.S. Sheriffs.” Journalism Studies 21(12): 1609–26.

Olson, Michael P., and Andrew R. Stone. 2022. “The Incumbency Advantage in Judicial Elections: Evidence from Partisan Trial Court Elections in Six U.S. States.” Political Behavior.

Robinson, Laurie O. 2020. “Five Years after Ferguson: Reflecting on Police Reform and What’s Ahead.” The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 687(1): 228–39.

Sances, Michael W. 2018. “Ideology and Vote Choice in U.S. Mayoral Elections: Evidence from Facebook Surveys.” Political Behavior 40(3): 737–62.

Sternberg Greene, Sara, and Kristen Renberg. “Judging Without a J.D.” Columbia Law Review.

Zoorob, Michael. 2020. “Going National: Immigration Enforcement and the Politicization of Local Police.” PS: Political Science & Politics 53(3): 421–26.

Zoorob, Michael. 2022. “There’s (Rarely) a New Sheriff in Town: The Incumbency Advantage for Local Law Enforcement.” Electoral Studies 80.