Unaccountable Sheriff Elections Provide Fertile Ground For A Growing Anti-Democratic Police Movement in Arizona

In the U.S., sheriffs wield immense responsibility in their communities. For many Americans, they are the first face of the law. While the laws that shape our lives may be debated and passed in a far-flung state Capitol or across the country in Washington, sheriffs tend to be the highest level of law enforcement tasked with carrying out this legislation in their local area. The “Constitutional Sheriffs” movement, founded in 2011 by then-Arizona sheriff Richard Mack, seeks to extend these responsibilities to powers beyond those granted by the rule of law by choosing whether or not to enforce and how to enforce various laws. Members of this movement have focused their efforts on right-wing talking points of the day: vaccine mandates, gun control legislation, and what they see as overly lax border patrol.

The name is unintentionally ironic: while the U.S. Constitution explicitly lays out a hierarchy of powers for various elected and unelected officials who carry out government functions, the Constitutional Sheriffs movement makes false claims about sheriffs having absolute powers above those generally reserved for judges and state or federal lawmakers. This movement seeks to make the sheriffs into judges – making decisions about the constitutionality of various laws – and into lawmakers, deciding to overturn the votes of state legislatures or U.S. congresspeople.

This anti-democratic movement became inextricably linked to the movement of election denialism around the 2020 election results, teaming up with True the Vote, a right-wing “vote monitoring” organization that repeatedly claimed that they possessed evidence of widespread voter fraud in the 2020 election, which they never released. Mack’s organization called on “local law enforcement agencies to work together to pursue investigations to determine the veracity of the ‘2000 Mules’ information.” Referencing the title of Dinesh D’Souza’s fraudulent documentary, which purports to find proof of fraud in the 2020 election lost by former President Donald Trump, they say the film presents “very compelling physical evidence.”

Dar Leaf, a Constitutional Sheriff in Barry County, Michigan, is an example of direct sabotage of the democratic process attempted by some members of the movement. In 2020, Leaf’s false assertion that vote-counting machines in Barry County flipped votes from Trump to Biden resulted in his office confiscating a seizing a voting machine. This move cast doubt on voting for future elections, and may lead to a loss of confidence in the democratic process. Leaf was placed under state investigation for his involvement in seizing the vote tabulator as part of an investigation into 2020 election fraud, but he was never charged, though some of his collaborators were. Leaf is currently refusing a subpoena ordering the release of materials he collected in his investigation.

The movement also has deep ties to the January 6 attack on the Capitol – founder Mack was a member of the Oath Keepers group, a militia currently under investigation for seditious conspiracy in relation to the Capitol breach.

Arizona, where Mack once served as the Graham County sheriff, is the birthplace of the Constitutional Sheriffs movement. This is not surprising given Arizona, and Western states more generally, have a long history of “rogue” sheriffs with large national profiles. Former Maricopa County sheriff Joe Arpaio was made nationally famous for a series of cruel stunts like forcing prisoners to eat rotten food and became a figurehead for right-wing sheriffs across the county. However, until recently, it was unclear exactly how widespread the newer Constitutional Sheriffs movement was among law enforcement in the state.

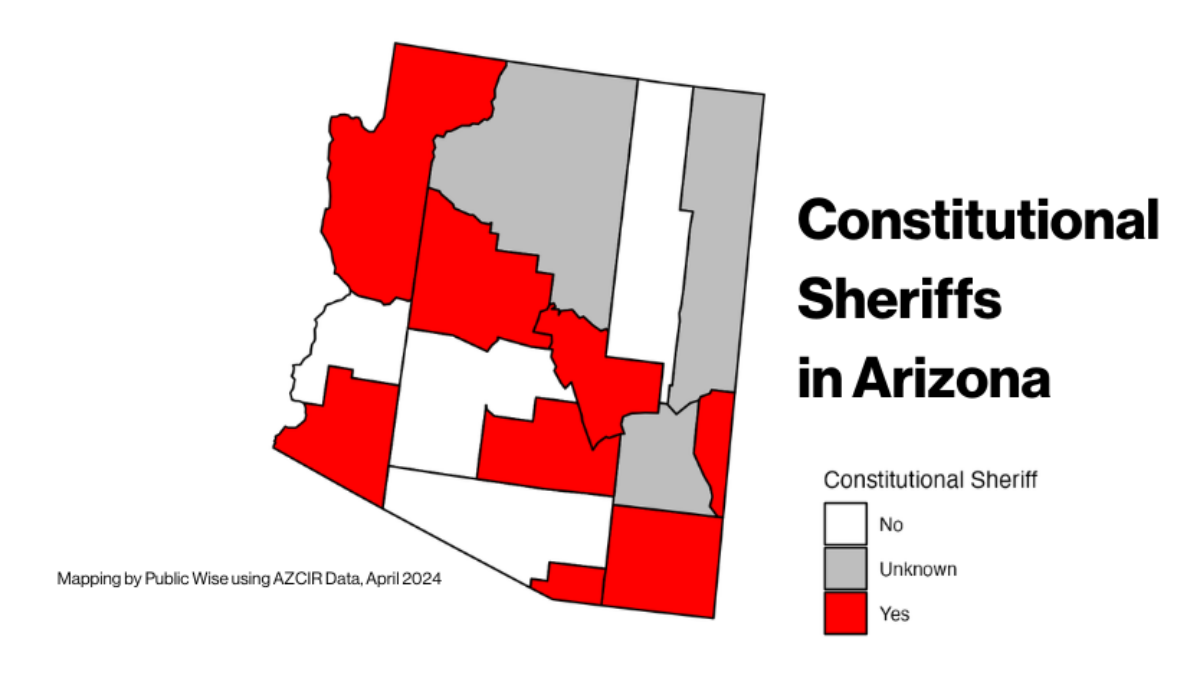

Last fall, The Arizona Center for Investigative Reporting (AZCIR) undertook an in-depth investigation in which they identified over half of Arizona’s sheriffs as part of the movement. In total, sheriffs affiliated with the movement have jurisdiction over one-fifth of Arizona residents. This means over 1.5 million Arizonans live under the law enforcement regimes of sheriffs who think they are above the rule of laws implemented by elected legislatures. That half the state’s sheriffs are Constitutional Sheriffs but only a fifth of the state’s population lives under their jurisdiction is reflective of the fact that Constitutional Sheriffs in Arizona are much more likely to represent less populous communities.

Beyond being undemocratic on the basis of rejecting the decisions of other elected officials like Governors, state legislators, and even the President of the United States, the way these officials get elected presents issues for democracy. Local races, like those of sheriffs, suffer from notoriously low turnout rates. Moreover, candidates often run unopposed. Once a sheriff is elected, it is hard to remove them from office because sheriffs have a substantial incumbency advantage in elections: An incumbent sheriff has a “45 percentage point boost in the probability of winning the next election – far exceeding the advantages of other local offices,” according to social scientist Michael Zoorob. On average, sheriffs hold office for twice as long as appointed police chiefs.

Arizona sheriffs are elected on the same ballot as the President, likely boosting turnout for these races when compared to other states. Yet sheriff elections in Arizona still suffer from anti-democratic dynamics that may have facilitated this movement’s rise to power, namely races in which candidates run opposed and low turnout.

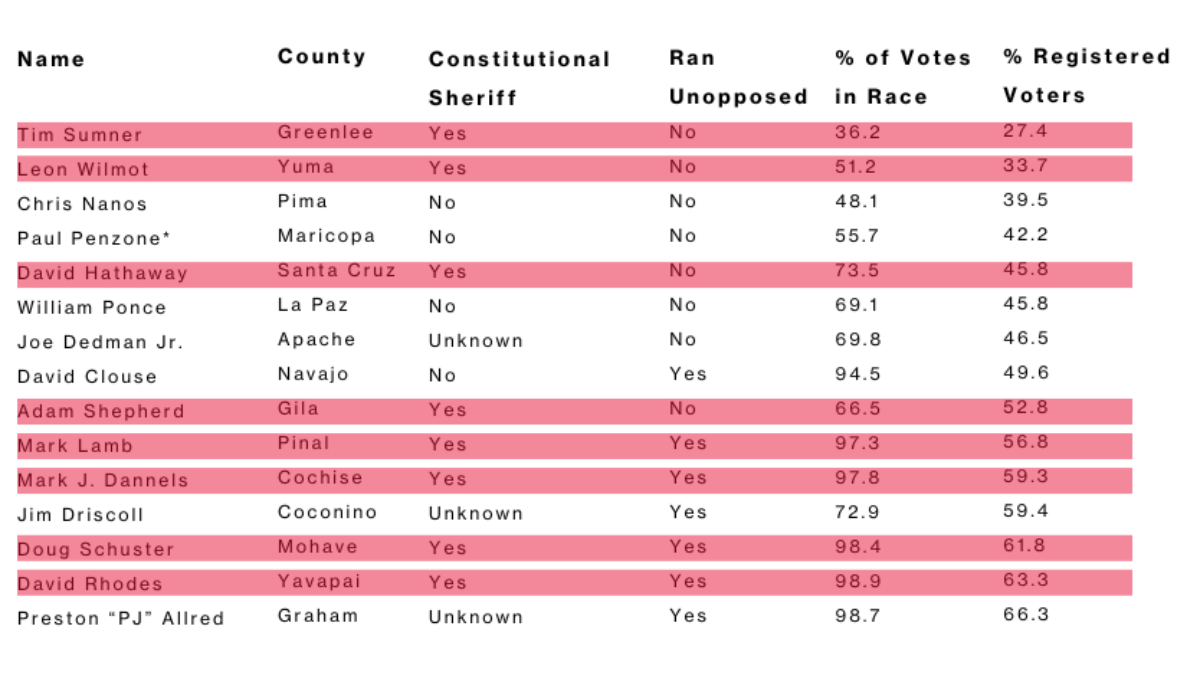

In the recent 2020 election, which brought the current set of Arizona sheriffs into office,1 7 out of 15 sheriffs ran unopposed, 4 of which were identified as having ties to the Constitutional Sheriffs’ movement.

Among the remaining four Constitutional Sheriffs who ran in races with an opponent, only one, Adam Shepard, who won with 66% of voters in his race in Gila County, was elected by a majority of registered voters (53%). Santa Cruz County Sheriff David Hathaway won with 46% of registered voters, close to half. But due to low turnout, two of these Sheriffs won their races with a relatively small percentage of registered voters in their county. In Greenlee County, Tim Sumner won with 1,333 votes – just 27% of registered voters in his county,2 and in Yuma County, Leon Wilmot received votes from just 34% of registered voters.

Otherwise stated, a Public Wise analysis found that all but one of the Constitutional Sheriffs in Arizona were elected either by a minority of registered voters or in races where they had no opponent. The low turnout and lack of attention paid to these small local races have opened up a gap where a profoundly undemocratic movement has been able to take and retain control of powerful offices with little to no accountability or oversight from American voters.

Most sheriff races in the U.S. are less competitive and less representative than races higher on the ballot. Our analysis in Arizona found that sheriffs affiliated with this Constitutional Sheriffs movement came to office with somewhat lower electoral accountability than sheriffs who are not. 50% of Arizona’s Constitutional Sheriffs ran unopposed, whereas only 42% of non-Constitutional Sheriffs did. Among Arizona’s 8 sheriffs who ran in competitive races, non-Constitutional Sheriffs were elected by an average of 44.8% of the electorate in their counties, while an average 40% of the electorate had voted for the sheriff in counties where a Constitutional Sheriff is in power.3

Part of the electoral crisis in sheriff accountability is due to legal structures: Journalist Jessica Pishko, in her year-long investigation into laws around sheriff accountability, found that sheriffs “lack even the most basic independent oversight and supervision,” particularly in the South and Southwest.

But it is also due to information and media failings, in particular in rural communities: Communications professor Lindsey Meek’s research has shown that smaller county newspapers do not provide as much comprehensive coverage of candidates for sheriff, and in particular regarding professional misconduct and the current or past Sheriff’s Department operations, such as prisoners’ treatment or budgets. A voter in Arizona who wants to find out about their local sheriffs’ positions, and in particular their relationship with the Constitutional Sheriffs’ movement, would, in some cases, find it to be a difficult task. For example, even when AZCIR or other media outlets reached out to ask about their positions on the movement, many sheriffs declined to stake out a position either way or hedged on an answer.

Yet some, like Mark Lamb, have made themselves public figureheads for the movement. Among the Arizona sheriffs not identified as being affiliated with the movement, however, only former Maricopa County Sheriff Paul Penzone and Pima County Sheriff Chris Nanos have explicitly condemned the movement, with the latter saying that the members had “hijacked law enforcement [and]… lost their integrity.”

But it is not just a failing of laws and media, but our elections themselves. Voters who do turn out for elections, especially in rural counties, often vote for an unchallenged incumbent candidate about whom they have very little actionable information. Even when candidates are forthcoming with their positions, voters may have trouble finding candidates who reflect their beliefs. Sheriffs’ races, often dominated by candidates with a more conservative ideology, do not typically feature debates on criminal justice policy reflective of the range of positions held by American voters. The Constitutional Sheriffs movement represents a potential threat to the rule of law and democratic representation in the United States, especially Arizona. Its ideas have now spread beyond the official affiliates of the group and into a wider network of sheriffs and other law enforcement officials across the nation. So far, this has not gotten the attention and concern it deserves. By drawing attention to the connection between local elections and law enforcement in the state, we at Public Wise hope to change that.

Footnotes

1 Maricopa Sheriff Penzone stepped down on January 12, 2024, and has been replaced by Russ Skinner, who was appointed. We leave Penzone in the analysis since the next election for Maricopa sheriff will not occur until November 2024. (AZ Central)

2 He won the largest share of votes in a four way race.

3 As a point of comparison for these numbers at the top of the ticket, the 2020 Presidential election saw Joe Biden win the US presidency with 48.3% of registered voters nationwide.